For a French tourist, an Orthodox church can feel both familiar and deeply foreign. Many unintentional mistakes come not from a lack of respect, but from applying Catholic or secular French norms to a different tradition. This guide goes beyond simple rules, explaining the ‘why’ behind Orthodox practices through cultural parallels you’ll recognize, transforming your visit from a potentially awkward encounter into a meaningful cultural experience.

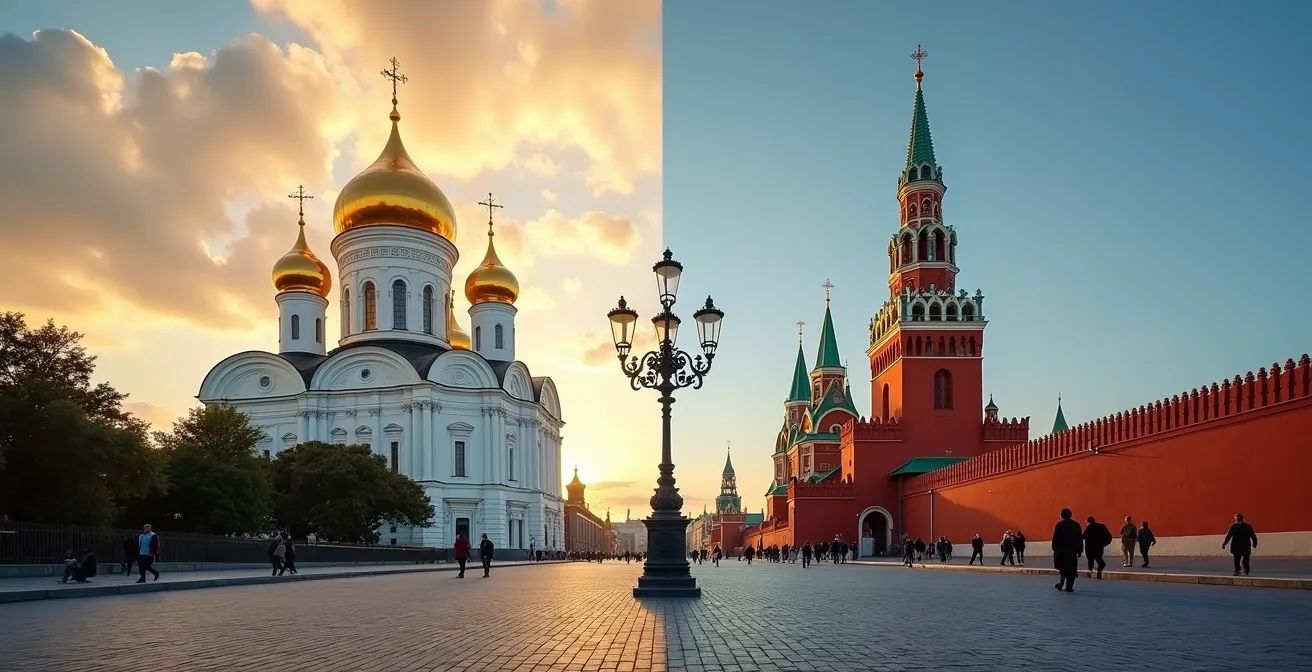

Stepping into an Orthodox church for the first time is a sensory immersion. The scent of incense, the golden glow of icons, the echo of choir chants—it’s a world away from the soaring, light-filled naves of a French Gothic cathedral. For the respectful French tourist, the desire to appreciate this beauty is often paired with a quiet anxiety: “Am I doing this right?” Questions about head coverings for women, whether to sit or stand, or how to navigate a service in progress are common. The typical advice to “dress modestly” is a start, but it barely scratches the surface.

The most significant cultural missteps happen when we assume the logic of our own background applies everywhere. A French visitor, accustomed to the structure of a Catholic Mass or the open public function of a monument like Notre-Dame, may misinterpret the fluid, deeply symbolic world of Orthodox worship. The key to avoiding faux-pas is not memorizing a list of rules, but understanding the theological and historical heart behind them. Why is the altar hidden? Why does the service seem to have no clear beginning or end? Why is a national monument like Saint Basil’s so surprisingly small inside?

This guide is built on a single premise: true respect comes from understanding. Instead of just telling you what to do, we will explain the *why*, often by drawing parallels with French history, architecture, and culture. By grasping the core concepts—the purpose of an iconostasis, the idea of worship as a “living stream,” and the distinction between a state monument and a devotional sanctuary—you can move with confidence and appreciation. This approach will not only ensure you show respect but will also enrich your visit, turning it into a genuine discovery.

This article will walk you through the most striking differences a French visitor will encounter. We will explore the unique architecture, the flow of the liturgy, the history behind famous cathedrals, and the intimate rituals that define the Orthodox faith, all framed to be understood from a French perspective.

Summary: A French Visitor’s Guide to Orthodox Churches: Understanding the Etiquette

- Why do Orthodox churches hide the altar behind a wall of icons?

- How long does an Orthodox Sunday mass really last?

- Christ the Savior vs. Kazan Cathedral: What is the difference in history?

- How to light a candle for the living vs. the dead in a Russian church?

- Why is the new Green Cathedral considered controversial by art critics?

- Saint Basil vs. Intercession Cathedral: What is the real name of the building?

- Novodevichy Cemetery: How to find Chekhov and Khrushchev’s graves?

- Why is the interior of Saint Basil’s so cramped compared to its exterior?

Why do Orthodox churches hide the altar behind a wall of icons?

The first and most striking feature for a visitor familiar with Catholic churches is the iconostasis—the ornate screen of icons that separates the nave (where the congregation stands) from the sanctuary (where the altar is). In a French cathedral, the eye is drawn directly to the high altar, an open and visible focal point. In an Orthodox church, the altar is deliberately veiled. This isn’t meant to exclude, but to symbolize a profound theological concept.

Think of the iconostasis as the veil in the ancient Temple of Jerusalem, which separated the Holy of Holies from the rest of the temple. It represents the boundary between the earthly realm (the nave) and the heavenly kingdom (the sanctuary). According to Orthodox belief, the icons are not just decorations; they are “windows into heaven.” As you stand before the iconostasis, you are surrounded by the saints and angels, the Church Triumphant, who are joining you in worship. The structure, as explained in studies on the topic, is seen as a bridge that connects the faithful on earth to the spiritual reality of heaven.

The central doors, known as the Beautiful Gates or Royal Doors, are opened only at specific moments during the Divine Liturgy, symbolizing Christ entering the world. Only clergy may pass through them. You will notice that the icon of Christ is always to the right of these gates, and the Theotokos (Mother of God) is always to the left. Understanding this symbolism is key: you are not being blocked from the service; you are being invited to contemplate the mystery of a heaven that is both revealed and concealed.

How long does an Orthodox Sunday mass really last?

If you arrive at an Orthodox church expecting a service that lasts for a neat 60 minutes, you will be very confused. A French visitor, used to the clear start and finish of a Catholic Mass, will instead find what feels like a continuous “living stream” of worship. An Orthodox Sunday service isn’t a single event but a series of services flowing into one another with no breaks. It often begins with Matins (Orthros), which can last an hour or more, followed immediately by the Divine Liturgy (the main Eucharistic service).

This is why you will see people coming and going throughout the service. In the Orthodox tradition, there is no stigma attached to arriving after the service has begun or leaving before it has officially concluded. Worshippers arrive when they can and stay for as long as they are able. The entire liturgical cycle on a Sunday can last for over three hours, and as some parishes explain to first-time visitors, the priest may be at the altar for this entire duration. This continuous flow is a fundamental difference from the more regimented Western tradition.

As a visitor, you are welcome to follow this custom. You can arrive, light a candle, stand for a portion of the liturgy, and leave quietly. However, it is considered respectful to stand during key moments: the reading of the Gospel, the Great Entrance (when the bread and wine are brought to the altar), the Anaphora (the Eucharistic prayer), and when the priest is censing the congregation. This explains why there are few, if any, pews. Worship is seen as an active, physical posture, though it is acceptable to rest against a wall or sit on benches if they are available, especially if you are not accustomed to standing for long periods.

Christ the Savior vs. Kazan Cathedral: What is the difference in history?

For a French tourist in Moscow, visiting the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and Kazan Cathedral on Red Square can feel like visiting two different worlds. One is a colossal, gleaming monument; the other is an intimate, jewel-box sanctuary. This is not unlike the difference between visiting Les Invalides and the basilica at Lourdes in France. One is a monument to national glory, the other a site of intimate, personal devotion.

The Cathedral of Christ the Savior is Russia’s national church, a monument built to commemorate the victory over Napoleon in 1812. Its history is deeply political: destroyed by Stalin to make way for a “Palace of the Soviets” that was never built, it was controversially and rapidly rebuilt in the 1990s as a symbol of Russia’s post-Soviet resurgence. It is used for major state ceremonies and official events, much like state functions might take place at the Panthéon or a military parade passes the Arc de Triomphe.

Kazan Cathedral, by contrast, is a place of pilgrimage. Its purpose is to house the Kazan Icon of the Mother of God, one of the most venerated icons in Russia. People come here not for a grand spectacle, but for personal prayer and to venerate a miracle-working icon. Its focus is spiritual continuity, surviving revolutions and political change. This table helps clarify the distinction for a French visitor:

| Aspect | Christ the Savior | Kazan Cathedral (Red Square) | French Parallel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | National monument, state ceremonies | Devotional worship, miraculous icon | Les Invalides vs. Lourdes |

| Historical Significance | Built to commemorate 1812 victory, destroyed by Stalin, rebuilt 1990s | Houses Kazan Icon of the Mother of God | Arc de Triomphe (victory) vs. Sacré-Cœur (devotion) |

| Political Symbolism | Post-Soviet Russian Orthodox resurgence | Pre-revolutionary faith continuity | Grande Arche (modern) vs. Notre-Dame (traditional) |

| Visitor Purpose | Official ceremonies, tourism | Personal prayer, icon veneration | State occasions vs. pilgrimage |

How to light a candle for the living vs. the dead in a Russian church?

Lighting a candle is one of the most common and accessible ways for any visitor, Orthodox or not, to participate in the life of the church. It is an offering, a physical manifestation of a prayer. However, a common point of confusion is that there are different places to light candles depending on whom the prayer is for. Unlike in many Catholic churches where candles are lit in a single area, Orthodox churches make a clear distinction between prayers for the living and prayers for the departed.

The lit candle itself is rich with symbolism. It represents the light of Christ dispelling darkness and the fiery intensity of our prayers ascending to God. The small donation you make when taking a candle is not a “purchase” but an offering that shows the seriousness of your intention and helps support the local parish. As a visitor, you are welcome to participate in this beautiful custom. You do not have to be an Orthodox Christian to light a candle and offer a silent prayer.

To do so correctly, follow these simple steps. First, locate the candle stands, which are usually near the entrance or in front of major icons. You will notice two different types of stands. For prayers for the health and well-being of the living, you should place your candle on one of the circular stands, often positioned before an icon of Christ or a particular saint. For prayers for the repose of the souls of the departed, you must find the specific rectangular table, which always has a crucifix on it. This special stand is called a kanun. As you place the candle, you can silently say the names of those for whom you are praying. Be mindful not to light candles during the Gospel reading or the sermon.

Why is the new Green Cathedral considered controversial by art critics?

The Main Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces, often called the “Green Cathedral” due to its khaki-green domes, is one of Russia’s most debated modern architectural projects. For a French visitor, the controversy might echo debates around the Centre Pompidou or the Pyramide du Louvre—a clash between radical modernity and a traditional setting. Here, the clash is between ancient Orthodox sacred aesthetics and overt modern military symbolism.

Art critics often describe it as a jarring fusion where sacred tradition is co-opted for nationalist purposes. The building is laden with military numerology: the diameter of the main dome is 19.45 meters, referencing the end of World War II in 1945; the height of a smaller dome is 14.18 meters, for the 1,418 days of the war. Most controversially, the floors and other elements are said to be made from metal melted down from captured Nazi tanks and weapons. This fusion of military hardware and sacred space is, for many, a step too far.

While traditional Orthodox cathedrals are designed to lift the soul towards a timeless, heavenly kingdom, this cathedral firmly roots its identity in earthly, military victory. The color palette of khaki green and metallic grey, the angular and severe forms, and the explicit military iconography create an aesthetic that many find more intimidating than spiritually uplifting. It represents a bold, and for some, problematic, statement about the relationship between church and state in modern Russia, making it a fascinating, if unsettling, destination for those interested in contemporary culture.

Saint Basil vs. Intercession Cathedral: What is the real name of the building?

Every French tourist knows the iconic, candy-colored domes of “Saint Basil’s Cathedral” on Red Square. Yet, almost no one knows its real name: The Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat. So why the popular nickname? The phenomenon is similar to how Parisians almost exclusively refer to the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Paris as simply “Sacré-Cœur,” letting a dedication or feature overshadow the official title.

In Moscow’s case, the popular name comes from a chapel that was added to the main structure to house the relics of Basil the Blessed. Basil, or Vasily, was a yurodivy, or “fool-for-Christ.” This is a unique and fascinating figure in Russian Orthodoxy with no direct equivalent in French sainthood. A yurodivy was a holy person who feigned madness and lived a radical, ascetic life outside of societal norms. They often spoke truth to power, and Basil himself was one of the few who dared to criticize the notoriously brutal Ivan the Terrible.

His sanctity and popularity with the common people were so immense that his chapel eventually gave its name to the entire cathedral complex in the popular imagination. Over time, “Saint Basil’s” became the universally accepted name. For tourists, using “Saint Basil’s” is perfectly fine and is what guides and locals use. But knowing the story of the humble, “mad” saint who upstaged a grand cathedral dedicated to the Mother of God adds a wonderful layer of cultural depth to your visit. It’s a testament to the power of popular piety over official decree.

Novodevichy Cemetery: How to find Chekhov and Khrushchev’s graves?

For a literary or history-minded visitor to Moscow, Novodevichy Cemetery is a must-see, the Russian equivalent of Paris’s famous Père Lachaise. While Père Lachaise holds the graves of artistic and bohemian figures like Morrison, Piaf, and Wilde, Novodevichy is the final resting place for Russia’s literary, political, and scientific elite, from the Soviet era to the present day. Navigating it can be a challenge, especially with most signage in Cyrillic, but finding the graves of its most famous residents is a rewarding pilgrimage.

The artistic styles of the monuments are a history lesson in themselves. You will see grand Soviet-realist sculptures alongside poignant, abstract memorials from the post-Stalinist thaw. This contrast is a key difference from the predominantly 19th-century romantic style of Père Lachaise.

| Feature | Novodevichy (Moscow) | Père Lachaise (Paris) |

|---|---|---|

| Founded | 1898 | 1804 |

| Notable Burials | Chekhov, Gogol, Khrushchev, Yeltsin | Morrison, Piaf, Chopin, Wilde |

| Artistic Graves | Soviet-era monuments, sculptures | 19th century romantic style |

| Navigation | Cyrillic signage, numbered sections | Latin signage, named divisions |

| Atmosphere | Political & literary history | Artistic & bohemian legacy |

Your Action Plan: Navigating Novodevichy Cemetery

- Obtain a map: Get a map at the entrance; even if it’s in Cyrillic, the section numbers are universal and essential for orientation.

- Learn key terms: Familiarize yourself with a few Cyrillic words: могила (mogila) = grave, писатель (pisatel) = writer, and политик (politik) = politician.

- Locate Chekhov: Head to Section 2 and look for signs to Чехов. His grave is a beautiful Art Nouveau monument adorned with theatrical masks, befitting the great playwright.

- Find Khrushchev: Go to Section 7 and search for the name Хрущёв. His grave is unmistakable—a powerful black-and-white abstract monument by the dissident sculptor Ernst Neizvestny, symbolizing his complex legacy.

- Visit respectfully: The best time to visit is on a weekday morning to avoid crowds. Respectful photography is allowed, but posing with graves is considered poor taste.

Key Takeaways

- Orthodox worship is a “living stream,” not a structured event. It is acceptable to arrive late or leave early.

- The iconostasis is not a barrier but a symbolic “window into heaven,” separating the earthly and divine realms.

- Many famous churches have popular nicknames that differ from their official titles, often revealing fascinating local history.

Why is the interior of Saint Basil’s so cramped compared to its exterior?

From the outside, Saint Basil’s Cathedral is a sprawling, fantastical explosion of color and shape. Visitors naturally expect its interior to be a vast, unified space, like the soaring nave of Reims or Amiens Cathedral. The reality is a shock: the inside is a labyrinth of small, narrow corridors connecting nine tiny, separate chapels. The feeling is cramped and intimate, not grand and expansive. This isn’t a design flaw; it’s a completely different architectural philosophy.

A French Gothic cathedral was designed for mass congregation, a single large space for the public to gather and witness the service. Saint Basil’s is better understood as a “bouquet of churches.” It is not one building but a collection of nine individual chapels clustered around a central tenth church. Each chapel was a private sacred space, intended for services for the royal family or specific prayer groups, not for large public gatherings. The grand exterior is a symbolic representation of the Heavenly Jerusalem, while the interior focuses on personal, intimate worship.

This architectural choice reflects a different vision of a church’s purpose. The expectation for large, open church interiors is a very Western, and particularly French, concept, shaped by centuries of Gothic design. This is true even for secular French visitors; the cultural image of a great church is one of immense interior volume. In fact, though approximately 6% of people in France regularly attend church, the architectural ideal of a grand, open nave remains the standard. Saint Basil’s challenges this expectation directly. Instead of looking for a wide-open space, visitors should appreciate the verticality of each small chapel, looking up at the spectacular frescoes that adorn each ceiling, much like one’s eye is drawn upward in the narrow confines of Paris’s Sainte-Chapelle.

Frequently Asked Questions About Visiting Orthodox Churches

Should tourists use ‘Saint Basil’s’ or the official name?

Using ‘Saint Basil’s’ is perfectly acceptable and universally understood by guides, locals, and tourism services. Knowing the official name, “Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat,” is simply an enriching piece of cultural knowledge.

Why did Saint Basil overshadow the Intercession dedication?

Saint Basil the Blessed was a beloved ‘fool-for-Christ’ (yurodivy) who was famous for daring to criticize Ivan the Terrible. His immense popularity meant that the chapel built to house his relics became more famous than the main cathedral it was attached to, and its name stuck in the popular imagination.

What does ‘on the Moat’ mean in the official name?

This is a simple geographical reference. The cathedral was built just outside the Kremlin walls, next to a defensive moat that existed at the time but has since been filled in.