Museums & Culture

Russia’s cultural landscape represents one of the most layered and complex tapestries in European history. From the golden domes of medieval cathedrals to the stark geometry of Soviet-era monuments, from world-class art collections rivaling the Louvre to underground metro stations designed as “palaces for the people,” the country offers cultural travelers an extraordinary depth of artistic and historical experiences. For French visitors accustomed to the refined elegance of Parisian museums or the historical continuity of French heritage sites, Russia presents a fascinating contrast: a cultural narrative marked by dramatic ruptures, radical transformations, and the coexistence of profoundly different aesthetic philosophies.

Understanding Russia’s museums and cultural heritage requires more than simply visiting individual sites. It demands grasping how religious tradition, imperial grandeur, and revolutionary ideology have successively shaped—and often violently reshaped—the nation’s artistic expression. This article provides a comprehensive foundation for navigating Russia’s cultural landscape, covering everything from selecting the right museums for first-time visitors to decoding the visual language of Orthodox architecture, from tracing the Romanov legacy to understanding the shift from classical to avant-garde art movements.

Choosing the Right Museums for Your Cultural Journey

Russia’s museum landscape can overwhelm even experienced cultural travelers. Moscow alone houses over 400 museums, ranging from world-renowned institutions to specialized collections tucked away in historic buildings. The key to a successful cultural visit lies in understanding the fundamental division between different types of museums and matching them to your interests.

Classic Versus Contemporary Art Spaces

The traditional museum experience centers on institutions like the Tretyakov Gallery, which houses the world’s most comprehensive collection of Russian art from medieval icons to early 20th-century masterpieces. These museums operate much like France’s Musée d’Orsay—chronologically organized, encyclopedic in scope, and essential for understanding artistic evolution. In contrast, contemporary art venues like the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art offer a radically different experience: experimental exhibitions, interactive installations, and a focus on current artistic dialogues rather than historical preservation.

State Museums Versus Private Galleries

State museums benefit from spectacular collections accumulated over centuries, often housed in architectural landmarks themselves. However, they can also feel institutional, with rigid visitor flows and conventional curatorial approaches. Private galleries, which have flourished in recent decades, offer more intimate encounters with art, often featuring cutting-edge Russian and international artists overlooked by larger institutions. For French visitors familiar with both the Louvre and smaller Marais galleries, this distinction will feel natural.

Practical Selection Criteria

When planning your cultural itinerary, consider these factors:

- Time available: Major museums like the Hermitage require a full day minimum, while specialized collections can be explored in two hours

- Thematic interests: Whether you’re drawn to religious art, Soviet history, or avant-garde movements will dramatically shape your choices

- Language accessibility: Increasingly, major museums offer English audio guides and labels, but smaller venues may require Russian proficiency or a guide

- Crowd patterns: Like Versailles, popular sites face severe overcrowding during peak tourist seasons and weekends

Understanding Russian Religious Architecture and Heritage

Orthodox Christianity has shaped Russian visual culture more profoundly than any other force. Even visitors with no religious interest must grasp the basics of sacred architecture to understand countless monuments, from the Kremlin’s cathedrals to the Golden Ring towns—a circuit of ancient cities northeast of Moscow that preserve medieval religious architecture much as French villages preserve Romanesque churches.

The Visual Language of Orthodox Churches

Russian churches communicate through a sophisticated symbolic system. The colors of domes carry specific meanings: gold signifies divine glory and is used for major feast churches, blue with gold stars honors the Virgin Mary, green represents the Holy Trinity or individual saints, while black marks monastic institutions. This color coding, once you understand it, transforms a simple walk through Moscow into a readable cultural text.

The iconostasis—the icon-covered screen separating the nave from the sanctuary—represents heaven’s gates. Unlike Catholic churches where congregations view the altar directly, Orthodox architecture creates a deliberate mystery, with priests disappearing behind this barrier during key liturgical moments. Understanding this fundamental difference helps explain why Russian churches feel so distinct from French cathedrals.

Architectural Styles and Their Evolution

The “tent-roof” style, unique to Russian architecture, features steep, pointed roofs resembling canvas tents rather than traditional domes. This indigenous form, exemplified by Kolomenskoye’s Ascension Church, developed in the 16th century before being suppressed by church authorities who demanded conformity to Byzantine models. The tension between native innovation and imported tradition runs throughout Russian architectural history.

Navigating Religious Tourism Respectfully

Active churches require modest dress and respectful behavior. Women should cover their heads and shoulders; men should remove hats. Photography is often prohibited or restricted. During services, maintain silence and stay in designated visitor areas. These expectations are stricter than in most French churches, reflecting Orthodoxy’s more conservative approach to sacred spaces.

Imperial History: From the Romanovs to Revolutionary Russia

The Romanov dynasty ruled Russia for three centuries, accumulating treasures and building monuments that now form the backbone of the country’s cultural heritage. Understanding this imperial legacy—and its violent end—provides essential context for countless museums and historic sites.

Tracing the Romanov Legacy

The Kremlin’s palace chambers, particularly the Faceted Chamber and Terem Palace interiors, showcase the evolution of court life from medieval Muscovy through Peter the Great’s westernizing reforms. These spaces demonstrate how Russia’s rulers oscillated between embracing European culture (much as French court style once dominated European nobility) and asserting distinctive Russian identity.

Estate museums like Kuskovo preserve the aristocratic lifestyle that paralleled France’s château culture. These summer residences, with their formal gardens, porcelain collections, and theatrical pavilions, reveal how Russia’s elite emulated European sophistication while adapting it to local conditions—including the necessity of building in wood rather than stone in many regions.

The Fabergé Phenomenon

The famous Fabergé eggs, scattered across museums worldwide but with important examples in Russia, represent the apex of imperial luxury. These Easter gifts from tsars to empresses combined technical virtuosity with whimsical design, encapsulating the refined excess of the dynasty’s final decades. Tracking down these objects across various collections has become a cultural treasure hunt for many visitors.

Revolutionary Rupture and the 1917 Divide

The abdication of Nicholas II and the subsequent Bolshevik Revolution created a dramatic before-and-after in Russian cultural history. Museums now navigate this divide carefully, presenting imperial splendor without necessarily endorsing monarchist politics, and acknowledging Soviet achievements while confronting Stalin-era repressions. This nuanced approach resembles how French museums present both royal grandeur and revolutionary heritage.

Decoding Russian Art Movements and Masterpieces

Russian art history follows a trajectory both parallel to and divergent from Western European movements. Understanding key artists and movements transforms museum visits from passive observation to active interpretation.

The Wanderers and Social Realism’s Early Roots

The “Wanderers” (Peredvizhniki) were 19th-century artists who rejected academic constraints to create socially conscious art depicting Russian life authentically. Their paintings—like Ilya Repin’s psychologically intense “Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan”—combine technical mastery with emotional impact and social commentary. These works resonate with French audiences familiar with Courbet’s realism or Millet’s peasant scenes, but carry distinctly Russian themes of suffering, spirituality, and national identity.

Landscape and Spiritual Vision

Russian landscape painting developed its own vocabulary, with artists like Isaac Levitan capturing the melancholic beauty of endless horizons, birch forests, and provincial stillness. These works aren’t simply pretty nature scenes—they express a philosophical relationship with landscape as spiritual experience, quite different from French Impressionism’s focus on light and perception.

The Avant-Garde Explosion

In the 1910s and 1920s, Russian artists led global avant-garde movements. Kandinsky, Malevich, and others pioneered abstraction while revolutionary fervor fueled radical experimentation. The Tretyakov Gallery’s new building houses major avant-garde works, though many masterpieces left Russia during the Soviet period and now reside in Western collections. Understanding this artistic explosion—and its brutal suppression under Stalin—is crucial for grasping 20th-century art history.

Socialist Realism and Propaganda Art

Stalin-era Socialist Realism imposed a rigid artistic doctrine: art must be realistic in form, socialist in content, and optimistic in spirit. While often dismissed as propaganda, these works reveal how totalitarian systems harness aesthetic power. Museums increasingly present Socialist Realism as a complex historical phenomenon rather than simply condemning it, allowing visitors to analyze how political ideology shapes artistic production.

Architectural Landmarks: From Constructivism to Stalin’s Empire

Moscow’s architecture tells the story of 20th-century Russia’s political upheavals through built form. The city serves as a three-dimensional textbook of architectural ideology, from revolutionary constructivism through Stalinist monumentalism.

Constructivist Architecture and Utopian Dreams

Early Soviet architects envisioned buildings that would reshape society itself. Constructivist structures featured geometric forms, industrial materials, and radical new building types like workers’ clubs and communal houses. Though many have been demolished or altered, surviving examples demonstrate how revolutionary politics generated revolutionary architecture.

The Seven Sisters and Stalinist Gothic

Stalin’s “Seven Sisters”—massive skyscrapers built in the late 1940s and 1950s—dominate Moscow’s skyline. These towers combine Art Deco verticality, Gothic ornamentation, and socialist symbolism into a unique style sometimes called “Stalinist Gothic” or “wedding cake architecture.” They represent Soviet power at its apex: grandiose, intimidating, and technically impressive. The psychological impact these buildings create resembles how Haussmann’s Paris boulevards assert authority through urban scale, but with an added layer of ideological messaging.

Deciphering Architectural Symbolism

Key monuments employ sophisticated symbolic programs. The Bolshoi Theatre’s reconstruction preserved its 19th-century imperial grandeur, including the famous quadriga statue of Apollo atop the portico. The massive chandelier inside—one of the world’s largest—simultaneously demonstrates technical prowess and creates theatrical magnificence. Reading these details transforms architectural viewing from casual observation to cultural analysis.

Experiencing Russian Performing Arts

Russian performing arts represent a living cultural tradition, not merely museum artifacts. The Bolshoi Ballet and other companies offer experiences that connect directly to Russia’s cultural heritage while remaining artistically vital.

Choosing the Right Performance

The Bolshoi offers both traditional productions (Swan Lake, The Nutcracker) and contemporary works. First-time visitors often choose classics to experience these ballets in their cultural home, much as one might prioritize Molière when visiting Paris. However, Russian companies also excel at dramatic ballets like Romeo and Juliet or contemporary choreography that showcases technical virtuosity in new contexts.

Selecting Seats and Understanding Venue Dynamics

Historic theaters like the Bolshoi feature traditional horseshoe configurations with multiple balcony levels. Sightlines and acoustics vary dramatically by location. Orchestra center seats provide intimacy but less comprehensive views of ensemble work. First balcony offers excellent perspectives at lower cost than premium orchestra seats—a practical consideration given that ticket prices can approach or exceed Opéra de Paris levels for popular performances.

Alternative Venues and Behind-the-Scenes Experiences

Beyond the Bolshoi, Moscow offers numerous performance venues with distinct characters. Smaller theaters provide more experimental programming and easier ticket availability. Some venues offer backstage tours, revealing technical operations that support the artistic magic—the massive stage machinery, costume workshops, and rehearsal spaces that make world-class performance possible.

Public Monuments and Cultural Spaces

Russia’s cultural heritage extends beyond formal museums into public squares, parks, and even the metro system. These spaces democratize culture, making artistic encounters part of daily urban life rather than segregating them in institutional settings.

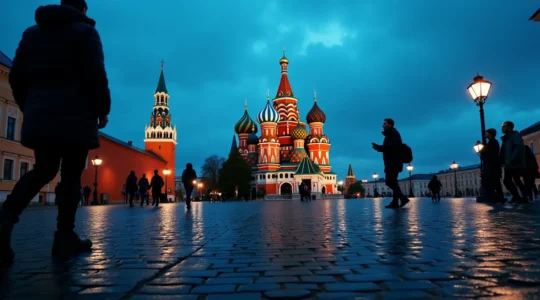

Red Square and the Kremlin Complex

Red Square functions as Russia’s symbolic center, comparable to the Place de la Concorde’s role in French national consciousness. The square brings together religious architecture (St. Basil’s Cathedral), political power (the Kremlin), commercial history (GUM department store), and revolutionary legacy (Lenin’s Mausoleum). Understanding how to navigate this complex—including timing your visit to the mausoleum, which maintains strict viewing schedules—requires planning but rewards visitors with concentrated cultural experiences.

Metro Stations as Underground Palaces

Moscow’s metro stations were designed as showcases of Soviet achievement, featuring marble, mosaics, chandeliers, and sculptural decoration that rival formal museums. Stations like Mayakovskaya (with ceiling mosaics depicting Soviet aviation) or Kiyevskaya (celebrating Ukrainian-Russian unity through elaborate decoration) can be “visited” during normal metro use. Observing how materials contrast—from polished granite to industrial concrete—across different

Why is Malevich’s “Black Square” at the New Tretyakov worth €10?

The €10 ticket for Malevich’s “Black Square” isn’t for a painting; it’s for an intellectual itinerary through 20th-century Russia’s artistic soul. Its value comes from its context: it is the destination of a journey that begins with 19th-century realism and…

Read more

Why Do Soviet Mosaics Depict a Future That Never Happened?

The dazzling mosaics of the Soviet Union are often dismissed as simple propaganda, but they are in fact a complex visual language for a future that was willed into existence and then lost. These artworks function as a “semiotic blueprint,”…

Read more

Decoding Russian Realism: A Guide to the Art, Politics, and Soul of a Lost Empire

Russian Realist paintings are more than just depictions of suffering; they are psychological ‘X-rays’ of an empire about to collapse. They reveal profound political dissent and social critique disguised as everyday genre scenes. They use the humble Russian landscape to…

Read more

Is the Acoustics of the Renovated Bolshoi Really Worse Than Before?

Contrary to the official narrative of a faithful ‘restoration,’ the Bolshoi Theatre’s six-year renovation created a sonically new instrument. The debate is not about ‘better’ or ‘worse,’ but about a fundamental shift in acoustic philosophy. The project traded the historic…

Read more

Did Ivan the Terrible Really Blind the Architects of Saint Basil’s?

The story that Ivan the Terrible blinded the architects of Saint Basil’s Cathedral is a powerful legend, but historically false. Historical records show the lead architect, Postnik Yakovlev, went on to design other significant structures after Saint Basil’s was completed….

Read more

Why is the interior of Saint Basil’s so cramped compared to its exterior?

Contrary to the Western expectation of a grand, unified nave, Saint Basil’s Cathedral was never designed for large congregations. Its seemingly cramped interior is a deliberate architectural choice, representing a symbolic map of the Heavenly Jerusalem. The collection of small,…

Read more

Why is Lenin’s body still preserved on Red Square after 100 years?

Many see Lenin’s Mausoleum as a macabre relic of a bygone era. However, this analysis reveals it as an active political instrument, meticulously maintained to stage Russia’s unresolved dialogue with its Soviet past. From its rigid visitor rules to the…

Read more

Romanov history tour: Which museums depict the Imperial era best?

To truly understand the Romanovs, one must look beyond the splendours of St. Petersburg and decode the dramatic saga hidden within Moscow’s historic sites. Moscow served as the dynasty’s spiritual heart, the source of its divine legitimacy, a fact reflected…

Read more

The Insider’s Guide to Buying Bolshoi Tickets: Secure Your Seat Without Broker Fees

Securing Bolshoi tickets isn’t about being lucky; it’s about understanding a system designed to be challenging for outsiders. The official website is your only truly safe option, but requires precise timing and a clear strategy to navigate its sales windows….

Read more

Why are Moscow’s cathedral domes shaped like onions?

The iconic onion shape of Russian church domes is not a clever trick to shed snow. It’s a powerful visual manifesto of Russia’s spiritual and national identity, born from a dynamic dialogue between Byzantine tradition, native wooden craftsmanship, and the…

Read more